No content results match your keyword.

Content

You have successfully logged out.

Not registered yet?

Oncology

Medication error is defined as any preventable event that may cause or lead to inappropriate medication use or patient harm while the medication is under the control of the health care professional, patient, or consumer.1 Medication errors can be classified by considering the types of errors occurring, such as wrong patient, dose, infusion rate, delivery route or medication. Medication errors may occur during any phase of the drug delivery process from prescription to drug administration and at anywhere medications are administered.2 Errors may occur with any medication; however, chemotherapy presents unique dangers due to narrow therapeutic indices, potential toxicity even at therapeutic dosages, complex regimens, and a vulnerable cancer patient population.3

“It may be part of human nature to err, but it is also part of human nature to create solutions, find better alternatives and meet the challenges ahead.”

Past studies have suggested that medication errors account for a significant percentage, if not a majority, of both total medical errors and medical misadventures resulting in mortality. Thus, medication errors are an important subgroup of medical errors due to their frequency, possibility of significant patient harm, and potential for prevention.3 A study revealed that antineoplastic agents were the second most common cause of fatal medication errors4 and antineoplastic drugs have been shown to be the drug-class which most commonly associated with medication error, only after anti-infective drugs.5

39% involved over- and underdosing, 21% involved schedule and timing errors, 18% involved wrong drugs, and 14% involved chemotherapy given to the wrong patient. Less common errors included infusion-rate errors, omission of drugs or hydration, and improper preparation of drugs. Ten percent of these errors required medical intervention and prolonged hospital stays.6

0%

involved over- and underdosing

0%

involved schedule and time errors

0%

involved wrong drugs

0%

involved chemotherapy given to the wrong patient

Generally speaking, wrong drug dosages can occur during all steps of the treatment process. During a 2-year period (2003-2004), Ford3 conducted a prospective study on the oncology ward of a large community hospital on medication errors. They identified 141 errors in total, there of 38 were classified as “wrong dose”. Of these, one occurred during ordering / transcription, 20 during dispersion and 17 during application. Additional 18 errors were “medication not given”.

In Adelaide (Australia) over a six-month period in 2014 and 2015, 10 cancer patients were given inadequate doses of the drug Cytarabine4, 7

With OncoSafety Remote Control®, oncological treatment and the administration of chemotherapy is digitally managed, controlled and documented. This reduces risks for cancer patients and helps oncology nurses to avoid errors done in the prescription, preparation or administration steps of cytostatics.

OncoSafety Remote Control®

0%

were infused too slowly

0%

were infused too fast

0%

were correctlv administered at the prescribed rate

Most of the chemotherapy regimes are given intravenously, i.e. directly into the venous system. Peripheral venous access may be suitable, however, given the high toxicity of the drugs, mostly central venous access are preferred.

A 6-year-old girl received intrathecal medication during her outpatient treatment. 3 days later she presented at the emergency room with pain in her neck and legs ...9

Some of the chemotherapy regimen require other patient access routes, such as intra-arterial access for isolated organ perfusion (e.g. for hepatic metastases) or intra-thecal applications (into the spinal canal, through a lumbar injection).

Cytarabine (Ara-C) can be used intrathecally for carcinomatous meningitis due to lymphoma or leukemia, and methotrexate can be given intrathecally for carcinomatous meningitis due to breast and bronchial cancers.10

For example, a patient with highly malignant non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma with cancerous meningitis would typically receive Vincristine 2 mg IV plus Methotrexate 10-15 mg intrathecally.

Some cancers can lead to metastases on the meninges, called carcinomatous meningitis. It occurs often in patients with leukemia or lymphoma, but also in breast cancer and bronchial cancer or malignant melanoma.

Patients with solid tumors plus carcinomatous meningitis have a bad prognosis. Without treatment, their mean survival time is mostly a few weeks only.

Vincristine is a vinca alkaloid antineoplastic agent intended for iv use only. Vincristine should never be administered subcutaneously, intramuscularly or intrathecally, as this results in necrosis.9 Accidental vincristine administration via the spinal route (intrathecally via a lumbar puncture or intraventricularly via an Ommaya reservoir) causes rapid sensory and motor dysfunction, usually followed by encephalopathy, coma, and death.11 Thus it has to be made sure that with combination chemotherapy, each drug is given into the correct patient access port.

Route delivery errors, of which intrathecal vincristine delivery is one example (there are many other examples such as intravenous delivery of benzathine penicillin, a galenic depot-formulation for intramuscular use), account for 5% of medication errors.

The specific risks of maladministration of vincristine sulfate were clearly recognized from the early experience in the 1960s.13 However, since then, 58 cases of intrathecal vincristine errors are known to have occurred which have been reviewed intensively.12,9 Out of these cases with inadvertent intrathecal administration of vincristine, only eight patients survived, most of them paralyzed.14 Specific case reports have been published.9, 14, 15

Safeguards used to stop certain drugs being given intrathecally 16

Most hospitals have strict rules to prevent the administration of vincristine and other vinca alkaloids into the cerebrospinal fluid. The rules at the Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children, London, for example, state that:

The universally Luer connector has been identified as a key element in ‘wrong route’ medication errors. Luer connectors are widely used for delivery of infusions. Literature shows that any patient having multiple access systems in place are exposed to higher risks of misconnections.17

To reduce the risk of wrong route medication errors the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) has developed standards for small-bore connectors, one being in the field of Neuraxial and Regional Anesthesia (ISO 80369-6). Devices that comply with the ISO 80369-6 standard are called NRFit®. They are 20 % smaller in diameter compared to Luer connectors and come with a yellow color coding.18

Read more

Errors are also costly in terms of opportunity costs. Dollars spent on having to repeat diagnostic tests or counteract adverse drug events are dollars unavailable for other purposes. Purchasers and patients pay for errors when insurance costs and copayments are inflated by services that would not have been necessary had proper care been provided. It is impossible for the nation to achieve the greatest value possible from the billions of dollars spent on medical care if the care contains errors.

But not all the costs can be directly measured. Errors are also costly in terms of loss of trust in the system by patients and diminished satisfaction by both patients and health professionals. Patients who experience a longer hospital stay or disability as a result of errors pay with physical and psychological discomfort. Healthcare professionals pay with loss of morale and frustration at not being able to provide the best care possible and society, in general, pay in terms of lost worker productivity, reduced school attendance by children, and lower levels of population health status.19

| Hospital stays | 62.248 € |

| Additional drugs | 23.658 € |

| Total annual cost | 92.248 € |

“Primum nil nocere. ”

“It may be part of human nature to err, but it is also part of human nature to create solutions, find better alternatives and meet the challenges ahead”. On their landmark publication in 1999, Kohn and colleagues of Institute of Medicine (IOM) called the entire health care sector to action.19 The IOM panel called for a transformation in the way health care professionals understand medical error by applying principles from cognitive psychology and human factors, the study of human performance in work environments. Improvements in aviation and other safety-oriented industries, such as chemical engineering, manufacturing, and nuclear power, showed that complex systems, rather than individual practitioners, were the primary sources of error and a target for improvement opportunities through simplification, standardization, and technology.21,30

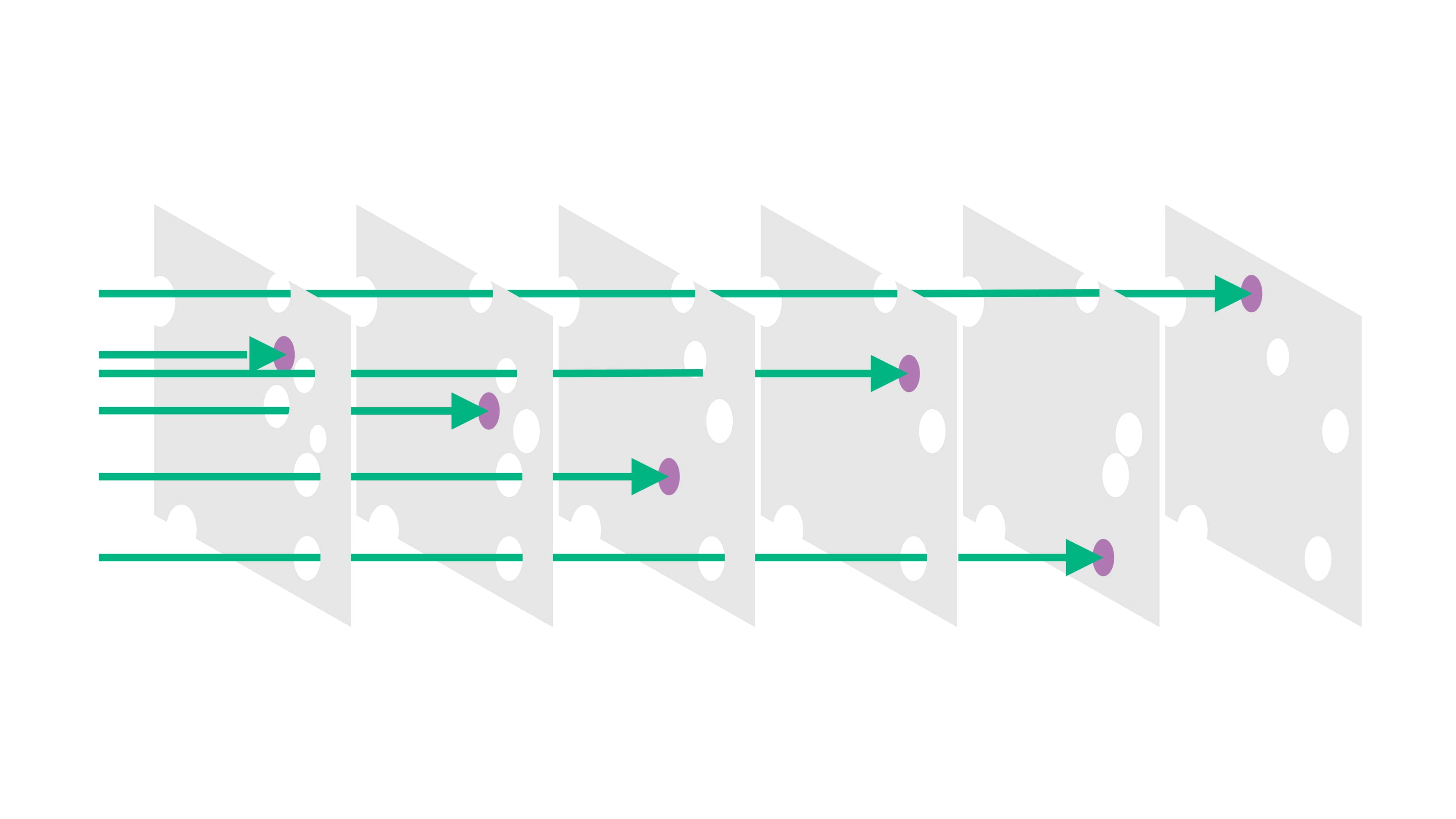

This has in the same year been called “Swiss Cheese Model”, referring to multiple layers of safety shields to prevent errors (holes in the cheese) to reach the patient.22,29 This model has been the conceptual foundation for the development of Critical Incident Reporting Systems for the reporting of and learning from critical incidents and near misses.

Label/Color Code Concept 23, 24 and a Barcode/Data Matrix to handle preparation data and close the loop to patient 25

/

IV pumps with intuitive handling and integrated drug database 26,27,28 additionally, compatibility databases 29

/

Comprehensive and interprofessional education and training of all involved staff 28,29,30,31as well as ward-based clinical pharmacists30,32

/

Different storage areas for important drugs (e.g. concentrated potassium chloride) 33, 38 and introduction of separate medication preparation rooms on ward 34

Incident reporting system 30, 35, 36

/

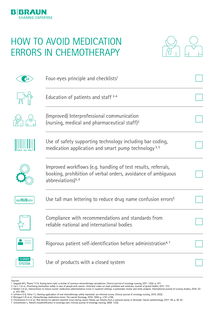

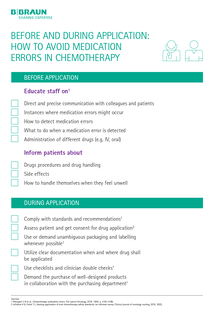

The American Society of Hospital Pharmacists (ASHP) consequentially developed a guideline on Preventing Medication Errors with Chemotherapy and Biotherapy in 2002 which has recently been updated.20 The guideline comprises recommendations for health care organizations, for multidisciplinary monitoring of medication use and verification, for prescribing systems and prescribers, for medication preparation and dispensing systems and roles for pharmacists, for medication administration systems and roles for nurses, for patient education, for manufacturers and regulatory agencies, and recommendations for identifying and managing medication errors.

Wrong administration techniques may comprise multiple aspects of the infusion. One example is discussed in the following:

„Paclitaxel is a chemotherapeutic drug frequently used for breast, ovarial and bronchial cancer. The drug is likely to form microbubbles and particulate matter. The suppliers recommend that an in-line IV filter should be used during the infusion of the agent (SmpC Paclitaxel). Not using the inline filter might result in particles being infused into the patient 37.“

Particles arising from infusion therapy may induce or aggravate inflammatory response syndromes. They have been shown to generate thrombosis, impair microcirculation, and modulate immune response. Sources of particles include components of infusion systems, incomplete reconstitution of solutions or drug incompatibility reactions. Up to one million particles may be infused per patient per day. In-line filters incorporated into infusion lines retain particles and thereby nearly entirely prevent their infusion.41

Others would be errors in assembling giving sets for secondary infusions with or without pumps, Luer access-devices unintentionally left open after use or needlestick injury due to needle-based manipulation.

Incidents involving patient misidentification (e.g., “wrong patient” errors) are not uncommon in oncology practice. Many of these incidents are near-miss or close-call situations that are averted at some point prior to reaching the patient. Patient misidentification is under-reported and its incidence is unknown.38

A nurse asked Mrs. Jackson to come back to the treatment room of an oncologist’s office for chemotherapy ...41

In 2002, the Joint Commission created its National Patient Safety Goals program. The No. 1 priority: improving the accuracy of patient identification. To meet this goal, health care providers use at least two patient identifiers — usually, name and date of birth. American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) and the Oncology Nursing Society collaborated to create chemotherapy administration safety standards to reduce the risk of error when providing adult patients with chemotherapy and give a framework for best practices in cancer care.39, 35

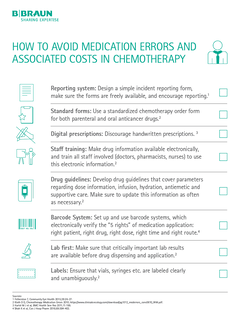

At a glance:42

Related topics

1. National Coordinating Council for Medical Error Reporting and Prevention (NCCMERP): What is a Medication Error. available at: https://www.nccmerp.org/about-medication-errors; accessed 02-23-2023.

2. The Boston Globe, 2004

3. Ford et al (2006): Study of Medication Errors on a Community Hospital Oncology Ward. Journal of Oncology Practice, 2006, 2 (4), 149-154. available at: https://ascopubs.org/doi/full/10.1200/jop.2006.2.4.149; accessed 02-23-2023.

4. ABC. (2015): South Australian Government launches inquiry over chemotherapy drug-dosing bungle. [online] available at: http://www.abc.net.au/news/2015-08-05/sa-government-launches-inquiry-over-chemotherapy- ungle/6673890; accessed 02-23-2023.

5. Lustig A. (2000): Medication error prevention by pharmacists – an Israeli solution. Pharmacy World and Science. 2000, 22 (1), 21–25.

6. Schulmeister L. (1999): Chemotherapy medication errors: descriptions, severity, and contributing factors. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1999; 26(6):1033-42.

7. MacIennan, L. (2016): Chemotherapy bungle at Adelaide hospitals due to clinical failures, SA Health Minister says. [online] available at: http://www.abc.net.au/news/2016-02-09/chemotherapy-bungle-at-adelaide-hospitals-under-review/7153168 accessed: 02-23-2023

8. Rooker JC, Gorard DA (2007): Errors of intravenous fluid infusion rates in medical inpatients. Clin Med. 2007;7: 482–5. available at: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/ec0d/acd06790eef073fb64a0678b74ca065e0516.pdf; accessed: 02-23-2023.

9. Hennipmann B. et al (2009): Intrathecal Vincristine. 3 Fatal Cases and a Review of the Literature. Journal Pediatric Hematol Oncol. 2009, 31 (11), 816-819.

10. Schulmeister L. (2006): Look-alike, sound-alike oncology medications. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2006, 10(1):35-41.

11. Bates DW et al (1995): Relationship between medication errors and adverse drug events. J Gen Intern Med 1995;10 (4):199-205

12. Noble D. (2010): The quest to eliminate intrathecal vinchristine errors: a 40-year journey. BMJ Quality & Safety 2010, 19, 323-326.

13. Toft B (2001): External Inquiry into the adverse incident that occurred at Queen’s Medical Centre, Nottingham, 4th January 2001, [online]. Available at: https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ukgwa/20080728185547/http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publications accessed: 02-23-2023

14. Arzneimittelkommission der deutschen Ärzteschaft (2005): Vincristin: Toedliche Zwischenfaelle nach versehentlicher intrathekaler Gabe. Deutsches Aerzteblatt 2005, 102,1615.

15. Dyer c (2001): Doctors suspended after injecting wrong drug into spine. BMJ 2001, 322 (7281). 257.

16. Kress R. et al. (2016): Unintentional Infusion of Phenylephrine into the Epidural Space. A&A Case Rep. 2016, 6(5),124-7.

17. International Organization for Standardization (2016): Small bore connectors for liquids and gases in healthcare applications -- Part 6: Connectors for neuraxial applications. [online] available at: https://www.iso.org/standard/50734.html accessed: 02-23-2023

18. Institute for Safe Medication Practices (2014): ISMP List of High-Alert Medications in Acute Care Settings [online] available at: https://www.ismp.org/sites/default/files/attachments/2018-01/highalertmedications%281%29.pdf accessed 06-07-2019

19. Ranchon et al. (2011): Chemotherapeutic errors in hospitalised cancer patients: attributable damage and extra costs. BMC Cancer 2011, 11:478.

20. Sasse M. et al. (2015): In-line Filtration Decreases Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome, Renal and Hematologic Dysfunction in Pediatric Cardiac Intensive Care Patients. Pediatric Cardiology 2015, 36 (6),1270–1278.

21. Reason, James (2000-). Human error: models and management. BMJ, 320 (7237): 768–770.

22. Weingart SN (2018): Chemotherapy medication errors. Lancet Oncol 2018, 19 (4), 191–99.

23. Parshuram CS, To T, Seto W, Trope A, Koren G, Laupacis A (2008) Systematic evaluation of errors occurring during the preparation of intravenous medication. CMAJ; 178(1): 42-8.

24. Cousins DH, Sabatier B, Begue D, Schmitt C, Hoppe-Tichy T (2005) Medication errors in intravenous drug preparation and administration: a multicentre audit in the UK, Germany and France. Qual Saf Health Care; 14(3): 190-5.

25. Taxis K, Barber N,(2003) Etnographic study of incidence and serverity of intravenoius drug errors. BMJ 326:684

26. Dehmel C, Braune S, Keymann G, Baehr M, Langebrake C, Hilgarth H, Nierhaus A, Dartsch D, Kluge S (2011) Do centrallly pre-pared solutions achieve more reliable drug concentrations than solutions prepared on the ward? Intensive Care Med 2010-00231. R3 in press.

27. Tissot E. Cornette C, Limat S, Maourand J, Becker M, Etievent J et al. (2003) Observational study of potential risk factors of medication administration errors. J Qual Improve 25(6):264-68

28. Vogel Kahmann I, Bürki R et al. (2003) Incompatibility reactions in the intensive care unit. Five years after implementation of a simple "color code system". Anasthesist 52(5):409-12

29. Valentin A, Capuzzo M, Guidet B, Moreno R, Metnitz B, Bauer P et al. (2009). Errors in adminstration of parental drugs in intensive care units: multinational prospective study. BMJ 338:b814. doi:10.1136/bmj.b814

30. Langebrake C, Hilgarth H (2010) Clinical pharmacists' interventions in a German University Hospital. Pharm World Svi 32(2):194-99

31. Taxis K (2005) Who is responsible for the safety of infusion devices? It's high time for action! QSHC 14(2):76

32. Rothschild JM, Keohane CA, Thompson S, Bates DW (2003) Intelligent Intravenous Infusion Pumps to improve Medication Administration Safety. AMIA Symposium Proceedings, p.992

33. Trissel LA (2011). Handbook on Injectable Drugs. 16th ed. Bethesda: American Society of Pharmacist.

34. Brigss J (2005) Strategies to reduce medication errors with reference to older adults. Best practice 9(4):1-6

35. Irajpour A, Farzi S, Saghaei M, Ravaghi H. Effect of interprofessional education of medication safety program on the medication error of physicians and nurses in the intensive care units. J Educ Health Promot. 2019 Oct 24;8:196.

36. Kane-Gill SL, Jacobi J, Rothschild JM (2010) Adverse drug events in intensive care units: Risk factors, impact and the role of team care. Crit Care Med 38(6): 83-89

37. Etchells E, Juurllink D, Levinson W (2008) Medication Errors: the human factor. CMAJ 178(1):63

38. Huckels-Baumgart S, Baumgart A, Buschmann U, Schüpfer G, Manser T. Separate Medication Preparation Rooms Reduce Interruptions and Medication Errors in the Hospital Setting: A Prospective Observational Study. J Patient Saf. 2021 Apr 1;17(3):e161-e168.

39. Smeulers M, Verweij L, Maaskant JM, de Boer M, Krediet CT, Nieveen van Dijkum EJ, Vermeulen H. (2015) Quality indicators for safe medication preparation and administration: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2015 Apr 17;10(4):e0122695. doi: 10.1371

40. Jones JH, Treiber L (2010) When 5 rights Go Wrong. J Nurs Care Qual 25:240-247

41. Schulmeister L (2007): Patient Misidentification in Oncology. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing 2007, 12 (3), 495-498. Available at: https://cjon.ons.org/cjon/12/3/patient-misidentification-oncology-care accessed: 02-23-2023

42. Schulmeister L (2002): Searching for Information for Presentations and Publications. Clinical Nurse Specialist, 2002, 16 (2); 79-84

43. Goldspiel B, Hoffman JM, Griffith NL, et al. ASHP guidelines on preventing medication errors with chemotherapy and biotherapy. Am J HealthSyst Pharm. 2015; 72:e6–35

Your feedback matters! Participate in our customer survey to help us enhance our website, products and services. Thank you for your support!